the New Normal

Location: 46 Linthorpe Rd, Middlesbrough, TS1 1RA

Dates: Fri 26 Sept - Sat 4 Oct (closed Mon 29 Sept & Tue 30 Sept)

Hours: Daily 10am-4pm (Sun 12-4pm)

Access: Step Free

Artists: Simon Poulter

-

Simon Poulter has an established national profile as both an artist and curator. His recent work has included a series of large scale commissions working with Minity, as part of the University of East Anglia Future and Form program. In 2019 he worked on a large-scale Heritage Fund project in Finsbury Park, London. This involved partnerships with the Museum of London, 2NQ and the Friends of Finsbury Park. The project consisted of an exhibition, new research and LIDAR scans of the park.

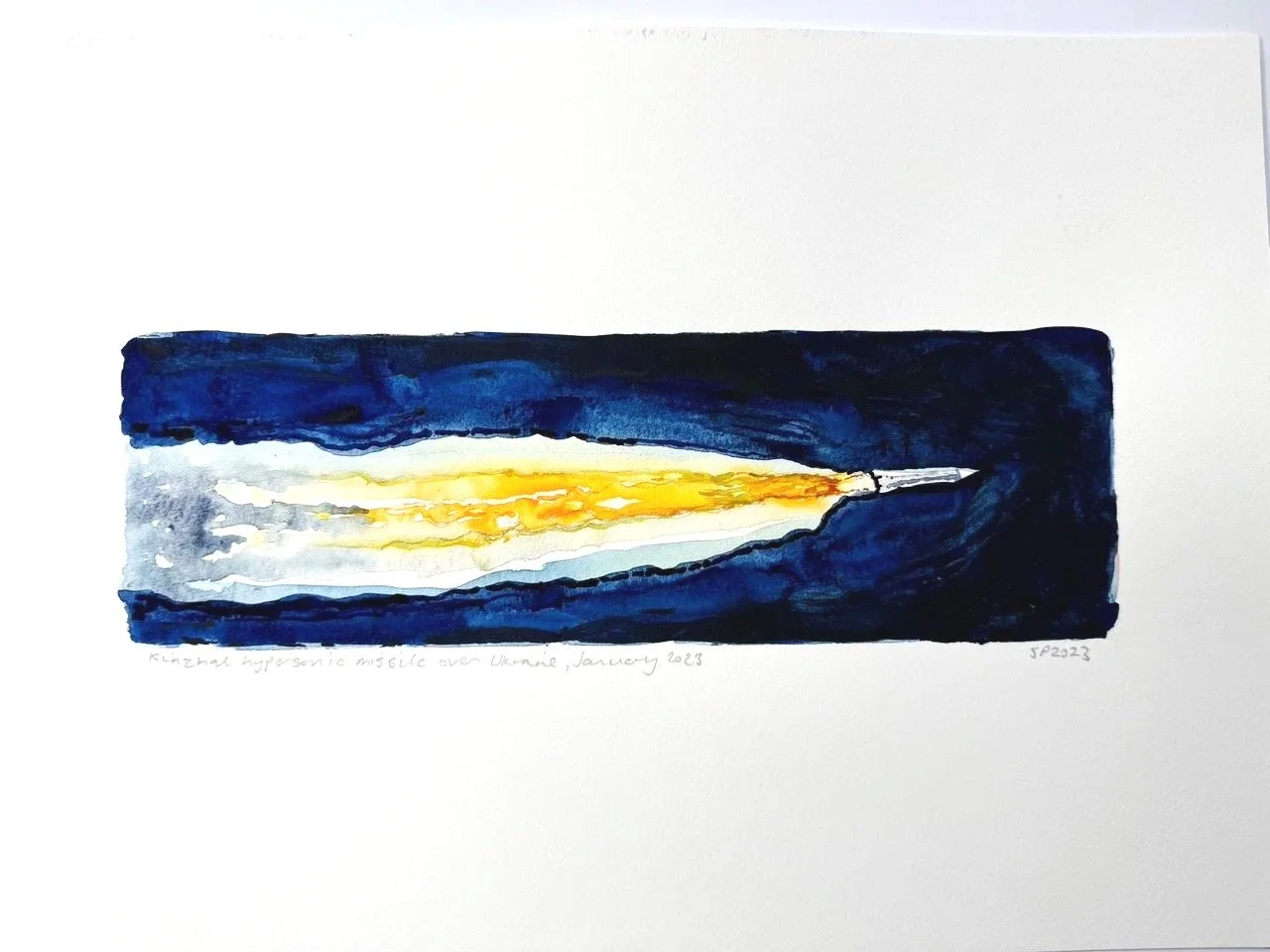

Poulter’s current focus is on two long range projects, called the ‘New Normal’ which consists of a series of paintings and online works. ‘New Normal’ has branched out in a number of directions, with over 100 watercolours of the Ukraine war. Poulter started pulling imagery from reddit groups with ex - military people discussing the conflict videos. Poulter started pulling imagery back from these videos and also adapting paintings from this. A key part of this project is to convey that Poulters intention is to slow things down and translate these digital feeds into a physical medium such as watercolour. Also, In the last three years, Simon has taught MA students at the University of Huddersfield, focusing on creative industries.

Instagram: @simonviralinfo

about the show.

The Flooded New Normal: Painting in a Post-Truth Society

The phrase The New Normal was first popularised in the early 2000s to describe the state into which a society settles after a seismic crisis—economic, political, or cultural. After the 2008 financial crash, and more recently, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the term re-emerged as a way to explain a recalibrated reality. In the UK, this new normal manifests through the mainstreaming of digital healthcare tools like E-Consult, the entrenchment of remote and hybrid working models, and the everyday use of Zoom—once novel, now mundane. Who even remembers Skype?

At the same time, the infrastructure of daily life has adapted: online shopping and food delivery are now central to urban existence. Across London, an army of precariously paid delivery drivers crisscross the streets, ferrying takeaways and groceries to isolated homes. These are the logistical arteries of a lifestyle born from lockdowns and continued by convenience.

But then, something deeper and more corrosive began to reshape this new normal.

In 2024, Donald Trump returned to the presidency. His political playbook accelerated a different kind of normalization—one rooted not in infrastructure or habits, but in disorientation. A strategy known as Flooding the Zone, popularized by Trump’s former advisor Steve Bannon, became emblematic of this shift. “Flood the zone with shit,” Bannon once declared—a brutal summary of a post-truth tactic where quantity trumps quality, and the deluge of information matters more than its accuracy.

In a post-truth society, facts are dethroned. What matters is not whether something is true, but whether it lands, sticks, or spreads. The truth becomes just another data point in an algorithmic maelstrom. As political theorist Jodi Dean describes in her notion of communicative capitalism, digital discourse is driven by metrics—likes, shares, subscriptions—not by deliberation or consensus. The attention economy doesn’t reward integrity; it rewards virality.

The emotional toll of this flood is profound. Rather than anchoring people in shared experiences or common understanding, the information torrent destabilizes. It nudges people into states of fear, anger, and suspicion. Where The New Normal seeks predictability and structure, Flooding the Zone aims for chaos and constant motion. It is an emotional deregulation project—engineered confusion at scale. And this is precisely how fascism gains ground: when a population loses its grasp on shared reality, it becomes reactive, tribal, and vulnerable. Like animals backed into a corner.

Not everyone has equal access to the tools of digital discourse—a smartphone, a reliable data stream—but the effects of the post-truth flood are widespread. In the UK, this manifests in strange rhetorical echoes. How, for instance, did a Labour Prime Minister end up referring to Britain as an “Island of Strangers”? The phrase, vaguely xenophobic and deeply populist, sounds more like a MAGA chant than Labour rhetoric. The answer is simple: the language of Trumpism has spread, carried by a kind of libidinal energy—an intoxicating affect of power and certainty—that others copy and paste into their own political scripts. This is not policy. It’s performance. The goal is to signal strength, to resonate with an imagined majority by exploiting the aesthetics of decisiveness.

The paintings I’m about to show you emerge from this contested terrain—from the flooded zone and the cultural debris of the post-truth world. New normals can be established, yes—but they are fragile. They can be swept away in an instant by a meme, a scandal, a new dominant narrative. Consider the UK’s post-war consensus—a 25-year period from 1945 to 1970, when a mixed economy, social welfare, and strong unions were seen as essential. That kind of long-term ideological settlement seems almost impossible now.

The images I paint are ripped from digital spaces—Reddit, YouTube, social media timelines. Sometimes they are translated directly into watercolour; other times they are collages, combinations, visual mash-ups. The familiar 16:9 screen ratio is intentionally disrupted, slit wide to fragment the coherence of the frame. Each painting is a slice—partial, mediated, provisional.

One image depicts Alexei Navalny. It is entirely imagined, a fabricated portrayal of his death. Why? Because I wanted to break through the Russian state’s kaleidoscope of propaganda, the endless hall of mirrors. In the post-truth zone, sometimes you paint a lie to reveal a deeper truth,

Some images echo fake medieval aesthetics, others are raw and rushed. I only have so many hours in a day. The work is not curated; it is responsive. If you’re caught in the flood, you don’t choose what you see—you react. As watercolours, these digital fragments gain a strange, vulnerable materiality. They are records of what has passed, but also invitations to reinterpret. Together, they form a visual story, but no two viewers will read it the same way. That’s the nature of the flooded new normal—it resists stable meaning.

Technically, the paintings follow traditional methods: washes layered upon washes, wet glazes, Fabriano paper. Some pieces are unfinished, rough, sketch-like. They speak through incompleteness. I include images from the Hamas massacre and the ongoing genocide in Palestine—not as commentary, but because these events cut deeply into the human condition. To ignore them would be dishonest.

And yes, the question of authenticity always lingers. When I contacted the Imperial War Museum about my Ukraine paintings, they responded curtly: they were only interested in lived experience. But what does that mean in a post-digital war? I haven’t been to Ukraine. But I’ve seen the feeds—soldiers on both sides filming their last minutes, drone strikes streamed like content, kills proudly displayed. It is a grotesque theatre, broadcast in high definition. I’m not there, but I am witnessing something real. I consider myself an online war artist.

Could I do all of this with software? Probably. It would be faster. More precise. But I’m not tempted. Watercolour remains seductive to me—an underdog medium associated with hobbyists and Sunday painters. It carries a fragility and modesty that digital tools can’t replicate.

These are watercolours of the zone being flooded. They are both witness and warning—a fragmented archive of our disintegrating consensus. In the post-truth world, where narrative shifts faster than memory can settle, they remind us of what we saw, what we scrolled past, and what we maybe, just maybe, believed—if only for a moment.